Building a team to counter school refusal

- October 15, 2019

- The REACH Institute

- Child mental health School refusal,

“When it comes to school refusal, getting all the adults on the same page is the bottom line,” said James Wallace, MD, a REACH faculty member. “Until you have that, you have nothing.”

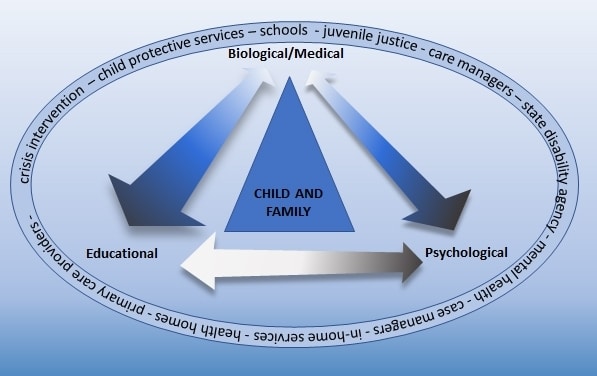

Dr. Wallace, who teaches child psychiatry at the University of Rochester (New York) Medical Center School of Medicine and Dentistry, described an approach to school refusal that unites primary care providers, schools, and mental health professionals in helping families make choices that support regular school attendance.

“An evidence-based approach to school refusal, and the anxiety or depression that usually underlie it, includes cognitive behavior therapy and sometimes medication,” said Dr. Wallace. “But there’s a third piece: getting all of the adults involved, including the parents, to address the social-emotional components of school attendance in a consistent way.”

Every pediatric clinician has seen patients who complain of stomachaches or other physical complaints that magically vanish on weekends or whose caregivers insist that school isn’t good for their child. “Then parents ask for a note so their child can receive home instruction. But that solution is rarely best for the child.”

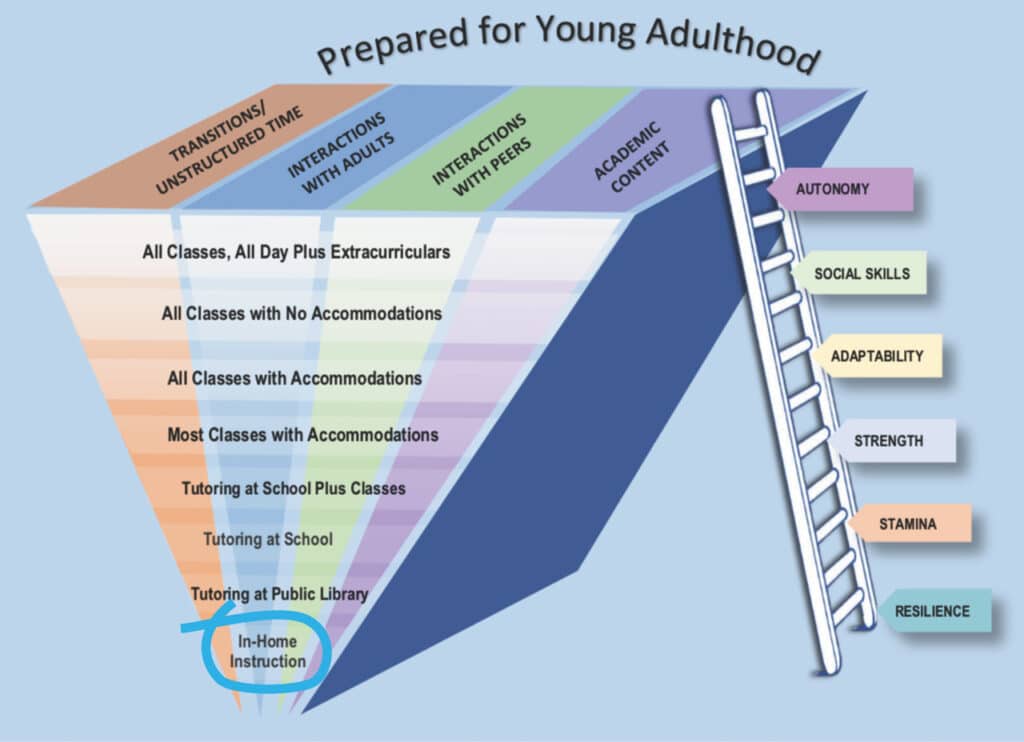

Clinicians can remind caregivers that academic content is only part of what students get out of school. Dr. Wallces uses the graphic below to emphasize that the ability to handle transitional and unstructured time at school and to interact with adults and with peers are also important in young people’s growth.

“Parents need to understand that home instruction might decrease the student’s distress, but it will increase the impairment. The farther we can keep students up the ladder of school engagement, the more prepared they are for adult life,” Dr. Wallace said.

The big challenge is to get caregivers to understand that accommodating children’s anxieties is not as helpful as pushing them to stretch past their comfort zone. “We can’t just buy into families’ perception that school is dangerous or unsupportive. Rather, school is an environment where kids learn to engage with the world,” said Dr. Wallace.

Dr. Wallace emphasized that a family’s perception of the issues at school is likely to be skewed, based mostly on what the child says. That’s why he recommends being in touch directly with the school. “You get the best and fullest picture of your patients from the people who see them 35 hours per week and who understand children.”

Dr. Wallace recommends making a regular practice of getting releases from parents and then talking to school personnel. “They’re usually thrilled to hear from us,” he said. “And talking with them is the only way you’ll get an accurate diagnosis.” When you call the school office, whoever picks up after you get through the phone tree can usually refer you to the staff member who knows the student best, whether that’s a teacher, counselor, or coach. Students in special education have a dedicated team, usually including a school psychologist or similar professional.

Similarly, Dr. Wallace suggests being in touch directly with any mental health professionals involved in the child’s care. Even if you referred the child to that professional previously, call for an update. “It’s stressful for parents to have to be the go-between” to transmit information from one healthcare professional to another.

Yes, this teamwork takes time. However, said Dr. Wallace, “If you can help families down this road of supporting young people to go to school, then they won’t be asking for another scan, another GI workup. You can accurately diagnose the mental health issue with the help of the school and really make a difference in the child’s life.”

“The bottom line,” he went on to say, “is that the team has power no individual part of the team has. You can really start to get young people back on track if you work together.”

RESOURCES

Parents sometimes cater to children’s anxiety about school because they want to protect their children from uncomfortable feelings. To reinforce the message that children must attend school, even when it’s uncomfortable, clinicians can recommend that caregivers read these articles on school refusal from Harvard Health and from Anxiety Canada.

Categories

- ADHD

- Anti-racism

- Anxiety

- Assessment & screening

- Autism

- Child mental health

- Coding

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- College transition

- Culturally responsive

- Depression

- Eating disorders

- Foster care

- Grief

- High-risk children & youth

- LGBTQIA

- Medication

- Parents

- Patient communication

- Pediatric primary care

- School refusal

- Sleep disorders

- Suicide

- Trauma

- Show All Categories

Register for courses

““It is great to be a part of a continuing medical education course with others within the same department. Change is always hard, but easier with teamwork.”